By Beth Richards, Literacy Interventionist, Reading Recovery Teacher, Guest Blogger

We often have brief windows of opportunity to capitalize on teachable moments that move our students forward as readers. Today's blog post is the first in a two-part series written to help you decide on the most important moves you can make when teaching students who are reading at levels A–C.

I have a recurring dream where I’m standing in front of a room filled with people. They are all staring at me intently, on the edge of their seats, waiting for me to say something brilliant. I open my mouth to speak, but I have no idea what to say.

As teachers, we are constantly in the spotlight and under intense amounts of pressure, and for me, one of the most anxiety-ridden decisions I have to make each day is what to choose as a teaching point for my students in guided reading groups or one-on-one lessons.

Examining the Text Structure in Leveled Books

It's important to examine texts at levels A–C as well as what students will be learning to control because if you truly understand the purpose, then you can keep that at the forefront of your teaching. Texts at levels A and B mostly have a simple sentence structure, strong picture support, and recurring high-frequency words.

It's important to examine texts at levels A–C as well as what students will be learning to control because if you truly understand the purpose, then you can keep that at the forefront of your teaching. Texts at levels A and B mostly have a simple sentence structure, strong picture support, and recurring high-frequency words.

In level A, the pattern remains the same throughout the book. In level B texts, usually, there is a change in pattern on the last page that the author anticipates the child may be able to control. In many level C texts, the pattern is eliminated and requires a stronger control of known words and more attention to visual information.

The point of this pattern change is to get kids to notice it. A storyline or plot may start to emerge in level C texts, whereas many level A and B texts are merely a listing or collection of things that are connected. Narrative and informational text at one of these levels, although repetitive and not very exciting at times, serve a purpose and are important for helping kids develop literacy behaviors.

Helping Students Practice Literacy Behaviors

A good rule of thumb to optimize reading practice with students is to look at what they are only partially able to do without your help, or what they are still neglecting, and tailor your teaching to that. For kids reading at levels A–C, a teaching point can be as simple as a quick demonstration or guided practice, explicitly showing students what you want them to do.

When teaching, you should take into consideration your students’ individual needs while directing your teaching point toward one of the following behaviors:

When teaching, you should take into consideration your students’ individual needs while directing your teaching point toward one of the following behaviors:

- left to right directionality

- maintaining one-to-one correspondence

- locating visual information to find something familiar

- noticing voice and print mismatch

- conventions in text, such as white space, capital letters, and punctuation

- concepts of letters and words

- exposure to high-frequency words they are working on controlling

Another teaching point can be praising something the child did well independently that they were struggling with. This lets the child know that what was just done is important and indicative of good reading, and they should continue to do that while reading. Keep reading for more details about some of the behaviors listed above with guidance on what to say when these are not yet controlled or neglected by students.

Left to Right Directionality

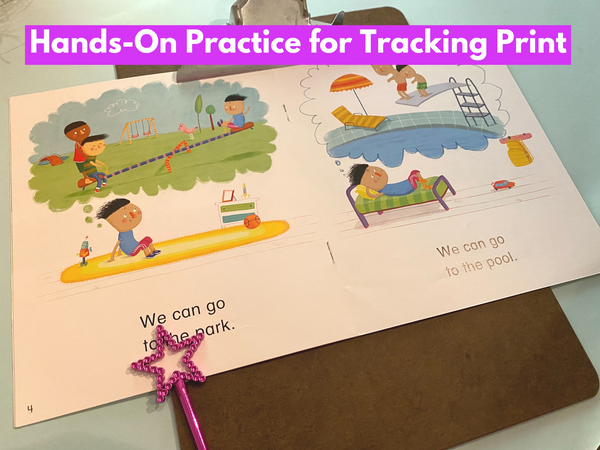

If a child is still flexible with their movement across a page of text (left to right, top to bottom), address this with your teaching point. A demonstration by you, or shared practice, will help teach the child the directionality rules that print follows. Next time, a brief reminder of where to start and which way to go prior to reading for this student will be helpful.

One-to-One Correspondence

If a child is still not matching one word on the page with one spoken word, focus your energy here. Often times, the trouble comes when students do not understand the purpose of the white space separating words. The other area they may be struggling with is multisyllabic words; they want to move their fingers for each syllable instead of each word. Since it is always easier for kids to learn on something known, try using their name (first or last) as an example by putting it in text, such as

Sarah can run

.

If a child is still not matching one word on the page with one spoken word, focus your energy here. Often times, the trouble comes when students do not understand the purpose of the white space separating words. The other area they may be struggling with is multisyllabic words; they want to move their fingers for each syllable instead of each word. Since it is always easier for kids to learn on something known, try using their name (first or last) as an example by putting it in text, such as

Sarah can run

.

When they say their name, even though it may have two or more syllables, they should know to leave their finger under their name until they’ve said it all. The same applies to other words, such as dinosaur or butterfly , which means you could say the following: Dinosaur has three parts. Keep your finger under it while you say all three parts, then move it to the next word.

Follow up this teaching by having multisyllabic words occur in the text (varying the multisyllabic word’s position within the sentence each time) for several days after. Keep in mind that your students may need support at first before you expect independent control.

Be sure to stay tuned for the second part of this blog post series for more guidance on teaching decisions you can make with students who are reading at levels A–C!

Beth has been teaching for seventeen years. She has taught kindergarten, third, and fourth grades in Wisconsin. For the last six years, she has been a literacy interventionist and Reading Recovery teacher and loves spending her days helping her students develop and share her love of reading.

Beth has been teaching for seventeen years. She has taught kindergarten, third, and fourth grades in Wisconsin. For the last six years, she has been a literacy interventionist and Reading Recovery teacher and loves spending her days helping her students develop and share her love of reading.