By Carla Bauer-Gonzalez, Reading Recovery Teacher, Guest Blogger

Recently, I was sitting down  with my Grade 1 Spanish intervention group, about to read Me Gusta el Futbol. We began the book orientation, and afterward, the first reading begins. What I observe of each reader is surprising; they were having the words run into one another. At first, I thought the problem was 1-1 voice/print matching. But I sensed it was something more. We had been battling this for several weeks, and my prompts didn’t seem to be working. What was I missing? I went to my guidebook, Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals (Clay, 2015), in search of answers. This passage jumped out at me: “Make sure the child can hear a distinction or difference between two sounds or two words before you try to teach him to see the difference. Don’t assume he can hear it. Start with large units, not the smallest ones, then separate some words out of phrases (heard or seen) or separate sounds or letters out of words” (Clay, 2016, p. 36)

with my Grade 1 Spanish intervention group, about to read Me Gusta el Futbol. We began the book orientation, and afterward, the first reading begins. What I observe of each reader is surprising; they were having the words run into one another. At first, I thought the problem was 1-1 voice/print matching. But I sensed it was something more. We had been battling this for several weeks, and my prompts didn’t seem to be working. What was I missing? I went to my guidebook, Literacy Lessons Designed for Individuals (Clay, 2015), in search of answers. This passage jumped out at me: “Make sure the child can hear a distinction or difference between two sounds or two words before you try to teach him to see the difference. Don’t assume he can hear it. Start with large units, not the smallest ones, then separate some words out of phrases (heard or seen) or separate sounds or letters out of words” (Clay, 2016, p. 36)

Was it possible that my students were unable to see word boundaries because they did not hear them in their oral language? It was a theory worth exploring.

Clay’s advice that we "Start with large units, not the smallest ones, then separate some words from phrases (heard or seen) or separate sounds or letters out of words” (p. 36), reminded me of a document I had come upon early on in my teaching career: A graphic organizer created by Emerald Dechant (1993). This graphic organizer identifies nine skills of phonological awareness and organizes them into three levels.

Because of the strong research-based correlation between phonemic awareness and literacy acquisition, early literacy instruction often focuses on phonemic awareness: a sub-skill of phonological awareness in which readers can distinguish each sound or phoneme in a word.

In the following paragraphs, I will share some of the things we did to develop word awareness and syllable awareness. Additionally, I will discuss the other essential sub-skills in phonological awareness: rhyming, initial consonant, alliteration, onset-rime, phonemic segmenting, blending, and manipulation.

Level 1: Building Awareness

- Word Awareness: is the first of three skills in Dechant’s Level 1, which also includes syllable awareness and rhyming awareness. In word awareness, this phonological unit is the spoken word, recognized as meaningful units in and of themselves.

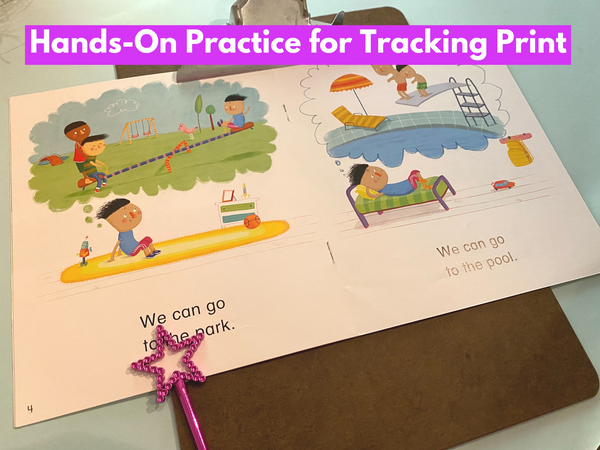

- One way to achieve word awareness is to have students tap the blank page in their writing journals for each word when planning their story. This helps them to distinguish words from other phonological units, such as syllables, and to anticipate the spacing of words on the written page. When the child taps the page three times for the word “perro,” we say “Júntalo. Perro es una palabra. Un toque en la página.” (Dog, together now, dog is one word. Tap the page).

- Syllable Awareness: requires the child to break meaningful units of language (words) into smaller parts that do not have meaning in and of themselves (syllables).

-

Syllable awareness can be developed nicely during writing activities when we ask children to clap the syllables of words they want to write. The more claps, the longer the word! El día de mascotas is great title for this excercise because it features many words with multiple syllables: perros, gatos and veterinario. You can say to students, “todo eso se junta sin espacios. VE-TER-I-NA-RI-O.” (All of this goes together with no spaces. Veterinarian.)

Syllable awareness can be developed nicely during writing activities when we ask children to clap the syllables of words they want to write. The more claps, the longer the word! El día de mascotas is great title for this excercise because it features many words with multiple syllables: perros, gatos and veterinario. You can say to students, “todo eso se junta sin espacios. VE-TER-I-NA-RI-O.” (All of this goes together with no spaces. Veterinarian.)

- Rhyme Awareness: Children with rhyme awareness can compare words that are phonologically similar after the first sound or part. Poetry or rhyming books are excellent resources for developing rhyme awareness.

Level 2: Furthering Awareness

- Initial Consonant and Alliteration: are the first two skills in Level 2 of Dechant’s chart. The first requires children to separate the initial sound from the whole word. The second (alliteration) requires children to recognize that many words begin with the same initial consonant.

- There is no shortage of activities for helping children begin to understand the concept of first letter sound and that many words begin with the same beginning sound. One of my favorites is Brinca para la P (Jump Up for P). Sing or recite a popular tongue twister or text that features a particular sound. Every time the child hears the 'P' sound, for example, he jumps. Another favorite are sound boxes, where a small boxes, such as a shoebox, that contain many objects that start with the 'P' sound.

- Onset Rime: at a purely phonological level, onset-rime awareness entails separating the first sound (or part in Spanish) from the rest of the word and identifying both. This has a direct application in reading and writing with the use of word families and orthographic patterns. Because words that share the same orthographic RIME also RHYME many of the activities used for rhyme awareness in Level 1 are applicable here. However, at a purely phonological level, the orthographic similarity is not required: We can use spoken words that RHYME even though they are not spelled with the same RIME.

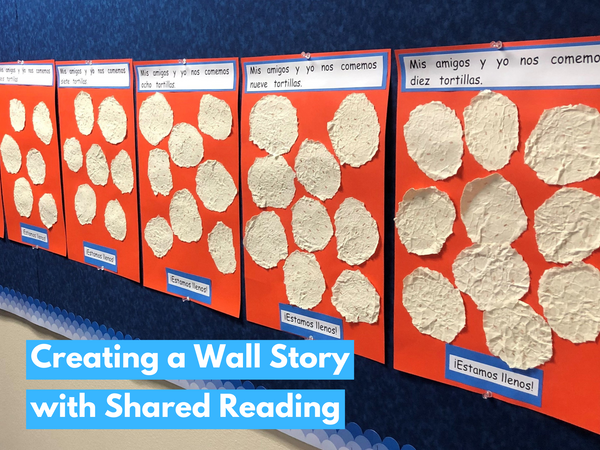

- After having the student read the rhyming sequence in Tierra (pictured), have them use rhyming words from the text to fill in the blanks in this phrase.

- Zapato – rato – Las dos acaban con _____ (ato).

- Mesa - limpieza - Las dos acaban con ____ (esa).

Level 3: Phonemic Awareness

In Level 3, we involve children in segmenting, blending, and manipulating the individual sounds of words, a subcategory of phonological awareness called phonemic awareness.

- Phonemic Segmentation: requires the child to tease out the individual sounds in whole words. This skill has a direct application to writing. In order to write a word, the child must first be able to hear and then record the individual sounds.

- Phonemic Blending: using phonemic blending, the child produces a whole word by putting together a sequence of individual sounds. This has a direct application to reading where he must recognize printed letters in words, say the corresponding audio, and blend these together.

- You can have students practice putting sounds together by having them sing a song; it can be as easy as putting words together to the tune of “If You’re Happy And You Know It," see an example of this below.

- Phonemic Manipulation: Phonemic manipulation is adding, deleting, or substituting of individual sounds in words to create new words. This phonological skill supports the use of analogy using known words to solve similar new words in both reading and writing.

Two months later, my students are making good progress. Our work with phonological awareness is paying off. While they have periodic lapses in one to one correspondence related to multisyllabic words, they are now able to monitor with the knowledge that “Es una palabra larga con cuatro partes que van todas juntas” (This is a long word with four parts that all go together).

There is some question as to whether phonemic awareness is necessary for a highly syllabic language such as Spanish, and more research is needed (Denton, et al. 2000 ) Even so, much research points to a strong correlation between phonological awareness and reading acquisition in Spanish. My personal experience corroborates this as I have seen clear benefits of using phonological awareness training for Spanish speaking readers first-hand.

~~~

Carla has been a teacher and staff developer in the field of bilingual education for 30 years. She has taught Kindergarten, Grade 1 and 2 in Wisconsin through the Milwaukee Public Schools Spanish Immersion and Dual-language Immersion programs. During this time she also worked at a national consultant for The Wright Group/McGraw Hill providing PD throughout the United States on balanced literacy in monolingual and bilingual programs. It was here that she first met Mrs. Wishy Washy, The Meanies, Dan the Flying Man, The Hungry Giant and the whole collection of Joy Cowley's fascinating characters! Currently, Carla is the Reading Recovery - Descubriendo La Lectura Teacher Leader in Waukesha Wisconsin.

Carla has been a teacher and staff developer in the field of bilingual education for 30 years. She has taught Kindergarten, Grade 1 and 2 in Wisconsin through the Milwaukee Public Schools Spanish Immersion and Dual-language Immersion programs. During this time she also worked at a national consultant for The Wright Group/McGraw Hill providing PD throughout the United States on balanced literacy in monolingual and bilingual programs. It was here that she first met Mrs. Wishy Washy, The Meanies, Dan the Flying Man, The Hungry Giant and the whole collection of Joy Cowley's fascinating characters! Currently, Carla is the Reading Recovery - Descubriendo La Lectura Teacher Leader in Waukesha Wisconsin.

![Developing Phonological Awareness in Emergent Spanish Readers [K–1]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/shutterstock_251933911_1024x1024.jpg?v=1586989281)

![6 Fun and Easy Activities to Practice Sequencing [Grades K-1]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post-5_bf1ae163-a998-4503-aa03-555b038d1b76_600x.png?v=1689961568)

![Leveraging Prior Knowledge Before Writing and Reading Practice [Grades 1–2]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post-4_600x.png?v=1689961965)