By Beth Richards, Literacy Interventionist, Reading Recovery Teacher, Guest Blogger

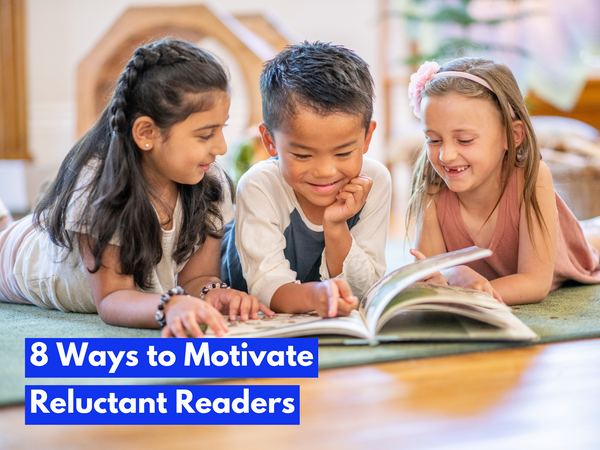

Have you ever observed a student who excitedly invents text while reading by telling a meaningful story with the help of illustrations, nuances of their oral language, and personal experiences? As children learn that they must also attend to the visual information of the text, many of them become overwhelmed or even confused. Today's blog post is the first of a two-part series written to suggest ways that you can help students access meaning during reading practice to boost their comprehension.

The integration of meaningful reading with visual information can be tricky for some, resulting in misconceptions that reading is merely an act of saying the words or figuring the words out. These students often have difficulty with retelling or comprehending a text because they are not approaching the act of reading as a “message-getting, problem-solving activity which increases in power and flexibility the more it is practised” (Clay 1991,6). They are stuck on how to keep meaning at the forefront while also attending to the visual.

Enna was a first grader with a split processing system. Sometimes, she made meaningful predictions during her reading that didn’t look right. Most often, however, she relied too heavily on visual information, substituting words that looked right but made no sense in the text. Her reading was slow, word by word with no meaningful phrases, and expressionless. You can predict, of course, that her comprehension of the text she was reading was minimal. Enna’s instruction needed to take a different direction. She needed to shift into a more integrated approach to reading.

In order to do that, I had to help her understand that her reading needed to be meaningful. Text selection for Enna needed to be deliberate. The orientation required her involvement as much as mine, and during reading, the problem-solving prompts and comments needed to remain focused on the meaning of the text. As we worked through those supports before and during reading, her reading fluency and comprehension improved as well, without that even being our focus.

Scaffolding is key. The following strategies can help improve comprehension with your younger readers by keeping meaning at the forefront of text interactions.

1. Be deliberate when selecting texts.

Clay states that “texts to which children can bring interpretations, and texts which are close to children’s oral language use, give them power over the learning tasks” (1991, 335). Choose a text with some familiarity with the student based on their own personal experiences or prior knowledge about the topic, characters, or theme. This is important so you can help the child make those meaningful real-world connections.

If you want to engage a child with a narrative text about a bad day, you can say the following:

Remember last week when you were upset and having a rough day? This book is called

A Bad Day

, and the main character is having a rough day just like you did! What are some things that had you so upset last week? Let’s look at the pictures and think about what might be making him so upset today.

If you want to engage a child with a narrative text about a bad day, you can say the following:

Remember last week when you were upset and having a rough day? This book is called

A Bad Day

, and the main character is having a rough day just like you did! What are some things that had you so upset last week? Let’s look at the pictures and think about what might be making him so upset today.

This sets up an opportunity not only for engagement but for empathy and understanding. The child will more easily be able to make meaningful predictions when she can access her own knowledge or personal experiences to think about the possibilities within the fiction book for kids.

2. Examine the text for problem-solving opportunities.

For Enna, she needed to shift to an integrated approach, which meant that at difficulty, I wanted her to be able to make a meaningful prediction first, and then check it against the visual information. That required the text to have opportunities for her to problem solve at places where she could use her meaning and structure to help predict.

For example, it’s easier for the child to anticipate a meaningful word if the word appears at the end of the sentence than at the beginning. So for Enna, the tricky parts needed to be ones where she could use the meaning and structure to help her predict, instead of solely relying on the visual information.

3. Provide and support a strong book orientation.

The purpose of the orientation is to get the child thinking about the meaning of the story. Always consider how you can provide the missing links for a child during the orientation in order to help them during reading. It should start with a simple sentence or two from you, giving the overview or gist of the story.

For example, if you want to introduce the narrative text

Clean Your Room, Nick!

you could say:

In this story, Nick can’t find any of his toys, and learns an important lesson.

Lyons (2003, 168) states that “the child must have an understanding of the main idea of the story in order to connect with the author’s message and gain meaning.” As the child opens the book and begins to look at the picture, make sure she is actively participating in the orientation by talking and making predictions.

For example, if you want to introduce the narrative text

Clean Your Room, Nick!

you could say:

In this story, Nick can’t find any of his toys, and learns an important lesson.

Lyons (2003, 168) states that “the child must have an understanding of the main idea of the story in order to connect with the author’s message and gain meaning.” As the child opens the book and begins to look at the picture, make sure she is actively participating in the orientation by talking and making predictions.

Often, in our attempts to help students, we inadvertently make them passive participants. It is critical for the child’s voice to be active in the orientation to engage her and support her reading comprehension. During this orientation, bring your voice in to help point out anything you think she may need to know to be successful. It may be a vocabulary word or concept that students may not have in their schema. It may also be practicing an unfamiliar language structure that is different from how a child speaks in everyday conversation, or perhaps just a structure she has not yet encountered in the text.

Here is an example of what you could say: In this story, each picture is happening on a different day. So this first page shows that on Monday, Nick asked his mom where his baseball glove is, and mom said, “Not in the closet.” You try saying that. Feel free to join in with the child, and encourage the use of that phrase on subsequent pages ( What do you think Mom will say when he asks where his watch is? ).

Think about the spots that you want the child to work at solving independently, and help with everything else. Clay states, “The first reading of the new book is not a test; it needs to be a successful reading” (2005, 91). A child is not going to be able to read the text in a meaningful way if there is too much problem-solving involved. You are freeing up some of that problem solving, the parts that the child is not yet ready for or do not match the child’s immediate goals, so that they can focus on the meaning and understand what they are reading.

Be sure to stay tuned for the second part of this blog post in which I'll describe more tips to improve reading comprehension with kids in kindergarten, first grade, and second grade!

Beth has been teaching for seventeen years. She has taught kindergarten, third, and fourth grades in Wisconsin. For the last six years, she has been a literacy interventionist and Reading Recovery teacher and loves spending her days helping her students develop and share her love of reading.

Beth has been teaching for seventeen years. She has taught kindergarten, third, and fourth grades in Wisconsin. For the last six years, she has been a literacy interventionist and Reading Recovery teacher and loves spending her days helping her students develop and share her love of reading.

![5 Tips to Improve Reading Comprehension [K–2], Part 1](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Main_image_Teacher_reading_to_students_Shutterstock_1177740694_Monkey_Business_Images_3263464d-7794-4095-a1cc-1d4a6d2a4de8_1024x1024.jpg?v=1689962009)